- Home

- Polis Loizou

The Way It Breaks Page 5

The Way It Breaks Read online

Page 5

When he got back home, his father sat him down to go through the family finances, and figure out how to diminish their debts. God rest her soul, the old girl’s only property was a house in the North lost in the War, not hers anymore but some Turk’s. Forget that. Her husband’s orchards had been sold off years before to pay a loan. The chance of being saved by the garage was slim. Thank God they would soon have Orestis’ higher salary and with it the prospect of progression, bonuses, perks. For now, the belts would have to stay tight, until the bank accounts could breathe. God willing the monthly interest didn’t kill them first.

In Orestis’ head was the refrain of his grandma’s tears. Her voice followed him everywhere, pathetic, apologizing for her existence, murmuring useless prayers. It would shame her to leave them with debt, but the old girl’s contract with life was terminated before she could buy herself out.

Seven

Days at the Harmonia passed more quickly than they ever had at the taverna. Orestis’ hands were always full, his brain always whirring. But while at the taverna he’d been a laden donkey, here he was a cog in a machine. No one stood around idle, and if they chatted football it was while their fingers machine-gunned the keyboards. Yiorgos kept his Front Desk staff occupied but he also entertained them with silly jokes. The work ethic spread to all departments, across all floors.

The pleasantness of the surroundings countered the intensity. If he had to warn a spoilt child, it wasn’t about ketchup on a grey floor, but about keeping ping-pong balls from flying into the bar amongst the palms, or over the bridge into the swimming pool, or into the lap of a tanning tourist. The scent of roses and freesias from porcelain vases. Sun-cream mixed with perfume. The clash of colours in cocktails and ice-cream sundaes. The symbiosis of textures, be it sofas or counters or drapes. This was an environment designed to stimulate, to gratify.

Once in a while, he’d encounter Thanos, and they’d exchange a friendly greeting. This mostly took place on the seafront, where the hotel’s lawn tapered into beach along a stone path. Orestis had found a good spot to eat his packed lunch; the subsidised meals at the hotel’s cafeteria exceeded his daily budget. Wary of getting dirt on his uniform, he’d sit on a smooth rock beneath the bow of a eucalyptus tree to stare out at the gleaming blue. Thanos would appear and stand close by to watch the sea, the swimmers, the cruise ships and tankers in the distance. He beheld it all as if it was both in his possession and a thing beyond his reach. It was the way Orestis’ grandma had looked in church: proud and cowed. God was yours but also no one’s. Whenever a private yacht drifted into view, the manager’s eyes would narrow. Orestis could only eat his tomato pasta and gaze at the object which, like the mermaid tourists in the sea, would stay forever on the horizon. He tried not to stare at the manager, though the man compelled him.

One of the bodies who frequented the beach was about Orestis’ age and colouring. That was where the likeness stopped. The swimmer’s was a dream physique, chest and abs curved like dunes. The rest of him was both concealed and exhibited by a pair of sleek black trunks. When he rose and sank in the water it was, to Orestis, as if a ghost of his future self were luring him forward. A cosmic cruelty. Thanos’ eyes turned to marble when he saw the swimmer. His body stiffened as if to keep him from acting out. Orestis put it down to a shared history between the men. Whatever it was, it was none of his business.

‘Some people are lucky,’ Thanos said once, with a lightness Orestis knew was feigned. ‘Getting to swim, all day every day…’

It had occurred to him that Thanos might be bent. Aside from his grooming, fine manners and love of beauty, which to Kostas and the rest of the family was proof enough, there was the sense that the manager’s smiles were softer to him than they should ever be between men.

Orestis filled the silence. ‘I wish I could.’

Thanos turned to appraise him. ‘You should.’

It was a running joke between Svetlana and Yiorgos that Orestis was a flirt. She would mimic him: Can I help you? in a sultry voice. He would blush, ashamed that someone had noticed these transactions, usually with the girlfriends of rich old men. His assistance for their grateful smiles. His recommendations in exchange for their curves peeked through damp sarongs and oversized shirts. Svetlana would giggle as she slapped his arm. Svetlana, who’d worked her way up the star ratings of hotels along the coast, to land this job after many years of graft.

Nothing was ever got for nothing. Somehow, Orestis knew, he was in debt to someone. And one day they would come to collect.

‘The sea is for everyone,’ said Thanos after a long, heavy silence.

✽✽✽

After his first Harmonia paycheque, and the final shift at the tavern, Orestis went back to see Pavlos. The hotel’s sporting facilities were free of charge for staff, but he felt obliged. It was the right thing to do.

Pavlos erupted with joy. ‘How’s it going, cuz? My old man says you’re working at the Armonia now.’

His dropout cousin had never learnt much English at school, so Orestis ignored the dropped H. Pavlos was one of the few people who’d never spat Charlie at him, or mocked his attempts at proper English. Even his grandma pursed her lips when she heard him speak the other tongue. Had Pavlos the chance or aptitude, he might’ve furthered his education, instead of spending his midnights prowling for potheads and sluts.

‘Yeah, re, it’s going well.’

‘When they make you Manager, make sure you get me in, yeah? Rich people love a personal trainer. Not like these villagers here who want me to train them for free.’

Orestis bristled. ‘Give me a few more weeks,’ he said, ‘let them get to know me, and I’ll ask around for jobs.’

Pavlos held one hand up for a shake and with the other slapped Orestis’ back. ‘My buddy.’ But the gesture burst the stench of weed in the air, and Orestis knew he would not be keeping his word.

For the next hour, they shot the breeze over a workout. Pavlos spotted him throughout: bench presses, cable curls, wrist curls, deadlifts. He threw in fifteen minutes of stretches at the end. It was better to work out in the morning, he said, contrary to what Orestis might assume. ‘We’re more productive early in the day.’ This from Pavlos, who’d spent his teen years waking up at four pm. ‘That way, you’re left with endorphins and higher energy. If you leave the gym till after work, you’ll grow tired or bored and never commit.’

The gym had been enforced in the Army, both by sergeants and peer pressure. After his conscription was over, Orestis’ motivation had faded with everything else. All that remained was a feeling of loss and waste.

‘It depends on my shifts,’ Orestis said.

His cousin grinned. ‘Fine. Just don’t leave it another month before your next visit, yeah?’

‘I won’t, I swear. And thanks, re – you didn’t have to stay and be my trainer. Not when you could get paid for it.’

‘E…’ Pavlos said, ‘you just do a good job at the Armonia and we’ll see about that.’

✽✽✽

Whereas Svetlana, following comments from a few Brits, was still learning to smile more and speak less curtly, the Front Desk manager took Orestis aside to praise him. ‘You have tact,’ said Yiorgos. ‘You never rub anyone the wrong way.’ At first, the praise was a gift, but it proved a wooden horse. Orestis was handed the worst guests, the most awkward scenarios. Why was Mr So-and-so-from-the-TV’s room smaller than his co-star’s? What use was the one squash court when it was always booked? If a maid had forgotten a hand-towel, it was Orestis who got yelled at. If a child had wandered off, it was Orestis who was to calm the parent. There were times when his anger rose so close to the surface he had to excuse himself to unleash it in the gents’. He’d slap himself, hard. After a moment or two, his focus would return. He’d lean back to let his breath go in and out. He’d wash his face. Up close on his reflection, he’d check his eyes, his lashes, skin, pores. He’d dissolve himself to a million bits. Eventually, his mood would ebb. He would whisper

his goals to himself, over and over. These were only tests to pass. Then he’d return to the Front Desk, and be ready with a smile for the next guest, the next obstacle, the next rung.

‘It was such a tough day at work,’ he’d tell his father over dinner.

But Kostas would rear his head like an angry horse. ‘Your generation is nothing but lazy yobs! Nobody wants to work a single fucking day! How many summers did I have to toil in the orange groves as a boy, for nothing but a few cents? Out there with the snakes. My hands were torn to shreds. For a few cents.’

‘I know, I’m not saying—’

‘I saved every coin! Every coin. Then I gave everything I had to that whore Englishwoman who saw me as a pocket.’

Head filling with brine, Orestis would steer the conversation to the less controversial topic of cars. Maserati, Lamborghini, anything guaranteed to lift the old man’s mood.

The one person he could confide in, without getting a kick in the balls, was Paris. At least once a week they’d meet outside the Harmonia – outside because Paris didn’t want to see up-close how the Other Half splurged. ‘Communist,’ Orestis would joke. But his friend was one to talk. Paris, whose family had funded his tuition in England and his jobless existence in Cyprus thereafter, was the Other Half. Together they’d stroll along the lamplit seafront, the moon tapping at the water, towards one of the cafés for a coffee or an ouzo. While Orestis sometimes fancied a flavoured syrup in his drink, he’d learned to condition himself. Any time he felt a craving for sugar he touched his flab. The growling stomach was silenced. These days, even Paris, who saw him once a week, noted a change. ‘You’ve lost weight,’ he’d say, matter-of-fact, lighting a cigarette. ‘A, wait, it’s gone to your arms.’

‘Look at my watch,’ Orestis would say, and demonstrate how tight it was on his wrist.

One night, Paris asked: ‘You seen Eva lately?’

Orestis hadn’t. The guilt was a sudden weight.

‘That’s funny. I figured she’d be all over you about the job.’

Orestis shrugged. ‘Looks like she’s forgotten me.’ He focused on stirring his drink.

‘Whatever you say.’ Paris took a long drag on his cigarette, eyes finding something outside in the dark to focus on.

Orestis didn’t want to think of Eva, or see her, or contact her. She had to be reassured of his gratitude without being encouraged. His only shield would be a girlfriend. It was the solution he kept coming back to, weak though it was. Until he had one, he’d keep his messages friendly but sporadic. Even if it took weeks, he would manage Eva Ioannidou out of his day-to-day.

Thankfully, one of her texts came with a lifeline: Don’t go having affairs with all those Russian girlfriends!!

He seized his chance: Too late.

From then on he would casually refer to imaginary ladies who threw themselves at him. In reality, his sole admirer was a Lebanese widow. She’d come to Cyprus as a refugee in the Eighties and now travelled from Paris four times a year, staying weeks at a time. She kissed his cheeks three times hello and praised him to the management. Though other guests smiled back, none had shown any interest beyond the matter of her stay. But if Eva saw him as a skirt-chaser, as most girls did in his school days, she might tell herself she’d never be enough for him. Her attentions would find another target.

When she asked him how he liked her Daddykins, Orestis replied: ‘To be honest, I’m afraid of him.’

It wasn’t untrue. The moment he saw Eva’s father step into the lobby, flanked by Thanos and the moody man from his interview, Orestis felt a chill. A portent. Aristos Ioannidou was a giant, dark hair grey at the sides and thin at the top. Sharp laughter lines gave him a mirthless air. His eyes were like a bird’s, flicking here, there, registering and apprising everything. He shared Eva’s large nose, not to mention that inexplicable magnetism. The self-assurance that comes with self-sufficiency, confidence stemming from comfort. The staff had been warned in advance of their boss’ visit, so the usual standards climbed a few notches. Uniforms pressed, spines upright, voices tuned to a sunnier key. Even Svetlana, who moaned about having to sound like Snow White, was turning on the charm. Orestis had worn his lucky underwear, a stupid new habit he couldn’t help. When he greeted his boss with a handshake, the man raised an eyebrow. ‘Yes,’ said Mr Ioannidou. ‘I remember you from my daughter’s school. You shook my hand then, too.’

The pause that followed filled Orestis with dread. But the man cracked a smile and slapped him on the back before moving on. Thanos thanked Orestis with his eyes, as did Yiorgos. When the boss moved on to other rooms and floors, Orestis’ colleagues pressed him about his connection to their boss. ‘It’s nothing,’ he told them. He and the owner’s daughter had known each other in his first school, the international one. He came to one of her birthday parties here. Orestis was quick to add that he’d been forced to leave the school shortly afterwards, due to a lack of funds.

Svetlana squinted but nodded.

At the end of his visit, Mr Ioannidou approached Orestis at the Front Desk. ‘I meant to ask: how’s your mother?’

Orestis froze. This was a joke. A nasty joke. The boss was angry with him, maybe because of Eva. Eva had complained, and Daddykins had decided to humiliate the cause of her pain in front of his colleagues.

But no. Mr Ioannidou’s tone had been friendly, his face was open. He had asked a question and was expecting a response. Orestis’ mother wasn’t a legend to everyone.

‘She’s fine, thank you.’ And for all he knew, she was.

Mr Ioannidou nodded. ‘She’s an interesting lady. Very knowledgable. Very polite.’ And with that, the visit was over.

Orestis felt hot. His body was drained, suddenly and totally shattered.

✽✽✽

His mother was born to Cypriot migrants in London. While back in the Motherland the remaining family were rebuilding their lives as refugees of the Turkish invasion, she and her parents and aunts were making weekly trips to the Brent Cross shopping centre. In the Eighties, when the debris of war had settled, she took a chance and accepted a job at a Cyprus-based shipping company. There she was in Lemesos, that city she’d heard so much about. She’d go for the occasional coffee with distant relatives in their hastily-erected council flats. She spoke her accented Greek to shopkeepers and received equal amounts of admiration and contempt from men on the streets. When she met Orestis’ dad, she was charmed enough to marry him. But, as she explained to her son one night, patting his wet hair dry, that’s when her island romance began to fade. ‘Your father changed,’ she said. He shouted if she so much as talked to another man, he criticised her skirts and shoes. Both her husband and mother-in-law demanded a child to continue their bloodline. It didn’t matter what she wanted, nor did they care if she was modern or inept. She began to feel the brunt of their tempers, not only her husband’s but also his mother’s. Meals became tense, mornings laden with gloom and failure. She would find herself staring out of the window at work, eight months pregnant because they relied on her salary. She would sigh at the sea and the ships that cruised away on it. She had her baby, and time went on. She couldn’t be prouder of Orestis, that much she assured him. She was glad to see her genes in him and almost nothing of that hateful other bloodline. Orestis’ manners and mannerisms were hers, as was the scale of his dreams. But it wasn’t enough to have a wonderful child. She craved escape. In time she heard that her mother, who’d flown to Cyprus twice a year since Orestis was born, had suffered an accident. She’d stepped into a London street when a motorbike sped through a red light and over her foot. The woman was laid up, with only her fragile old husband to care for her. She needed her daughter. This was her ticket out. Orestis’ mother kissed him through her tears at the airport, left for England, and never came back. On the phone, she implored him to come and join her. How could he? He was at school here. His friends, his father and grandmother, who loved him fiercely, his aunts and cousins, were all in Cyprus. His father would glower, then ta

ke the phone from him and hang it up. ‘If she loves you so much, she can come and get you,’ he’d say. Instead, she let Easter pass, and then the summer holidays, then Christmas, with only an intermittent phone call to remember her by. She sent him a ruler depicting the London skyline, which Orestis hid at the bottom of his school bag. Without the support of his mother’s salary, he was forced to leave the international grammar school for a Greek-speaking state one. His English dwindled – never completely, but enough to widen the trench between him and her. His London grandparents became too old to visit their homeland. His father’s and grandmother’s fury simmered to bile. Every so often a birthday card or postcard would be waiting in the mailbox at the gate, each one bearing the same words, in English: Love, Mum xx. In later years, with the advent of email, she took to sending him more frequent, detailed messages via his aunt. Lenia would print them off and sneak them to him on visits. It’s hard to explain how trapped I felt, his mother confessed in a particularly lengthy one. Cyprus oppressed me. The weight of the sun, the mosquitos, those flying cockroaches that scared me to death, people’s staring. There, I was The Charlie. The Englishwoman. The whore. To your father, I was always and only those things. Now she was back home in England, where she belonged. And she was happy. Free. A master of herself. Orestis didn’t know how to respond to that email, so he never did. The days simply slipped away. And all that was left now, where once was a sense of awe at the woman who’d appeared only briefly in the life she gave him, was resentment. Sometimes he gave in to nostalgia. A vague memory of sitting in the passenger seat as she drove, just the two of them on the highway in comfortable silence, brought a pain to his chest and throat. He swallowed it down and turned his mind to other things. It didn’t matter that she’d sent him a postcard once in a while. The truth was that his mother was happier now. And she’d never come to get him.

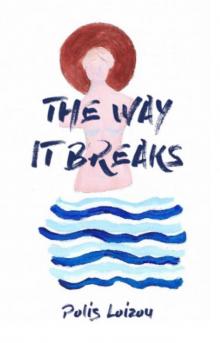

The Way It Breaks

The Way It Breaks